The best new writing and the greatest classics under one roof … in association with Forward Chess

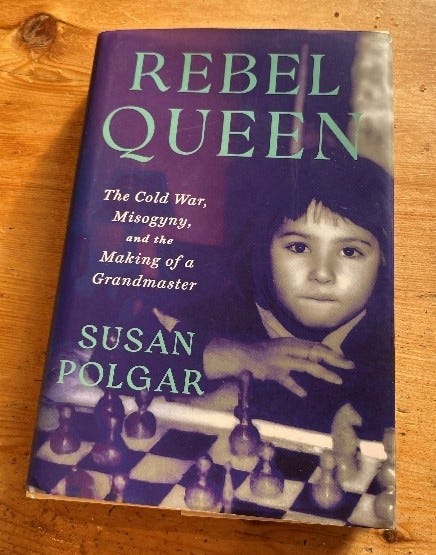

Rebel Queen by Susan Polgar (Hachette Book Group)

‘One of the reasons I was fighting so hard for the right to compete against men, after all, was so that my sisters – and all the girls who would come after them – wouldn’t have to face the same obstacles.’

Susan Polgar has lived a remarkable life, and fully does justice to her extraordinary story in this exceptional book. Once the strongest fifteen year old in the world of either gender, a former women’s world champion, and the first woman to earn the male version of the grandmaster title, her exploits are legendary. From her role in the successful Hungarian Olympic teams through to the part she played in coaching both her sisters and later at US universities, she now brings her journey to the page in Rebel Queen.

Susan Polgar has truly been a trailblazer and a role model for many female players who have followed in her footsteps. As she puts it, ‘If anything, the noticeable absence of women (in competitive chess) lit a fire in me. There was still a lot of history to be written for this game, and I was going to do my best to write it.’ The chess world is fortunate that the fire burnt as strongly as it did in Susan, as the obstacles were many. I was left with the feeling that in some ways the chess itself was easier than the battles with the Hungarian state and the pervading culture of sexism and misogyny she encountered and overcame, which is why this book is such an inspirational read.

It all started with Polgar’s father’s belief that ‘the key to fostering genius in young children was to create the opportunity for them to do what they love.’ Despite the resistance of the Hungarian authorities, he did this in spades, nurturing not just three brilliant chess players in Susan, Sofia and Judit, but also three thoroughly decent and well-rounded individuals. His home schooling methods may have been controversial, but the fact that Susan has nothing but praise for him and her mother after all these years shows that his approach worked on more than one level. Did it produce brilliant chess players? Of course! Did it also produce a loving family that remains close to this day? Absolutely! – and perhaps that is the most important facet of the Polgar legacy.

Susan Polgar’s exploits at the board, and the stories of the champions she meets (including having Bobby Fischer as a house guest), are beautifully told. Who wouldn’t empathise with someone who describes the first chess tournament they ever played in as follows? ‘I can hear the click-clacking of pieces against chess boards, the sound of old mechanical chess clocks being punched after each move, the dim of hushed conversations, the intermittent coughs and throat clearings that would echo through the room, the occasional squeak of a chair against the floor.’

Yet, what takes this book up a further notch, and probably explains the mainstream publishing deal, is that this is also a rites of passage story of the highest order. We learn a lot about Polgar’s personal life, with all its messy complications. The first love, who somehow omitted to tell her that he had three children, such that when the realisation dawned ‘At that moment, the man I had been so committed to for the last year and a half felt like a stranger.’

Then there was the husband who proposed after a brief courtship and by fax, only for it to ultimately become clear that they were incompatible. Polgar had been due to be in the World Trade Centre at the time of 9/11. A twist of fate meant that she wasn’t there but ‘Coming that close to death, and seeing with my own eyes how quickly it could all be over, filled me with a new sense of resolve,’ and she ended the relationship. Ultimately Polgar finds happiness when she marries Paul Truong. There are other anecdotes, such as learning to drive and getting the car stuck on a hill, that really add richness to her story. Polgar is a brilliant chess player, but she is also a flesh and blood human, rather than some sort of chess-playing automaton, and it is her willingness to share that makes this book so special.

The stain of antisemitism runs through Rebel Queen. All four of Polgar’s grandparents were Auschwitz survivors. As a child she asked her grandmother about the number tattooed on her arm. ‘The visible shift in her demeanour frightened me… “Oh, you’re too young to hear about any of that,” she said, trying to change the subject. “I’ll explain it to you when you are a little older.” She sat for a moment, composing herself. “I hope you never have to learn how much a human can endure.”’ There is often a sense that part of the reason why the Hungarian authorities are so unhelpful to the Polgars (as we will explore further shortly) is because they are seen as somehow ‘other’ and not ‘real’ Hungarians.

Her relationship with Bobby Fischer is inevitably compromised by his own antisemitism, which as we know existed despite Fischer’s own Jewish heritage. They initially become friends in the 1990s. Spassky is amongst the visitors when Fischer was staying with the Polgar family. As Susan notes, ‘Even though I had known Spassky for years by then, having both him and Bobby sitting at my parents’ dining room table discussing chess wasn’t something that seemed possible. They might have been arch-rivals, but they had long since become good buddies and were incredible company when together, always laughing and playfully arguing.’

Fischer has apparently changed his views on women, now acknowledging that it would be impossible to give knight odds. The work they do together to develop Fischer random chess is fascinating. Polgar also gives a more nuanced take than is sometimes reported as to Fischer’s thoughts on Kasparov and Karpov. Polgar notes that he had huge respect for them both as players, but could never be convinced that their games weren’t rigged, because ‘He just couldn’t believe that players of that calibre could miss ideas that seemed so obvious to him.’

Yet Fischer ‘… also had his dark side. Without warning, he would launch into some hateful diatribe about a global Jewish conspiracy.’ At one point Fischer tells Polgar that he doesn’t mean the Polgars when he rants in such a way, which is of course to misunderstand what antisemitism and its all-encompassing poison really is. Ultimately, ‘By the fall of 1994 … his antisemitic views had become harder for him to suppress, even around me… Now I had had enough. I would never stop caring about him and considered him a friend for the rest of his life, but I needed to get some distance.’ This is certainly a fascinating portrait of a deeply damaged individual and Polgar’s attempts to help him as best she could, before inevitably boundaries were crossed that could not be uncrossed.

Misogyny forms part of the book’s subtitle, and is another difficult undercurrent in Polgar’s story, although the very first resistance she meets is because of her age. She plays in her first tournament as a four year old, and some of the other parents were ‘…asking condescending questions about whether I really liked chess, or whether I’d rather be playing with toys. Why did I have to choose? And why did they care so much?’

She wins the Budapest Elementary Schools Championship District Qualifier with 10/10, which makes her ‘… a minor national celebrity,’ but it’s not enough to protect her from sexism’s curse. The Budapest authorities refuse to let her play in the finals; she arrives at the playing hall to find that she has been disqualified because she is a girl. ‘I spent the bus ride home crying to my father uncontrollably, begging him to go back and fix it. But there was nothing he could do. The tournament had started and I wasn’t going to be playing in it.’

It is impossible to do justice in this review to the scale of the Hungarian authorities’ attempts to thwart the Polgars during their careers. Reading of the misogyny they faced for years, and the deeply troubling account of the sexual assault on Susan Polgar at a chess tournament, it is impossible not to be moved by the struggles they encountered.

As well as the institutions (shame on FIDE for at one point adding a hundred rating points to every female player other than Susan Polgar, so that she would no longer be the number 1 woman in the world, and shame on the Hungarian state for the multiple travel bans), individuals’ prejudices are also highlighted. To talk of lighter moments in such a context does not feel quite right, but it did make me laugh to learn that Ljubomir Ljubojevic, who was the world number 6 at the time, objected to her and Maia Chiburdanidze playing at Bilbao, only to then lose to both of them.

Being the eldest of three sisters brings with it its own special responsibilities. Susan writes that ‘I can still remember my mother arriving home from the hospital in her yellow- and brown-checkered dress, carrying Judit in her arms.’ She recalls that with both Sofia and Judit ‘I would often find myself serving as part babysitter, part chess coach, spending hours a week in our apartment’s back room teaching them endgame technique or analyzing classic games by Capablanca or Alexander Alekhine or Fischer.’

You would think that there must have been some sort of sibling rivalry. It can’t be easy to be as brilliant at something as Susan is, and to see your younger sister Judit overtake you as the highest-rated female player on the planet at just twelve years old. Yet there is no hint of resentment. Susan writes that ‘Celebrity can be a lonely condition, but we were going through it together, at an age when we could all really enjoy it.’ Ultimately, ‘Professional chess was still a boys’ club, and in many ways it remains so today. But at least I had cleared a path for my sisters and made it just a little bit easier for other girls to follow our lead.’ The enduring strength of the bond between the Polgar sisters is very clear, and that matters much more than the fact that Judit was the stronger player.

The Cold War is another feature of Rebel Queen. Polgar recalls that during her first visit to England she was struck by the range of goods in the shops. ‘There were women in gorgeous colourful dresses and men in well-tailored suits… People just didn’t have this kind of choice or variety back in Hungary, and they certainly did not express themselves through what they wore. It was against the official ideology to stand out too much…’. When she visits London, ‘At night, the town was lit up in bright neon lights – which would never have happened back home, where electricity was rationed and the city mostly went dark every evening.’ Yet Polgar’s life coincides with the end of the Cold War, and the end of a repressive and controlling ideology. As Polgar puts it, ‘… when Hungary removed the barbed-wire fence along our border with Austria it was the very first puncture in the Iron Curtain…’

There are so many other aspects of Susan Polgar’s book that I would like to have featured here in more detail, had space permitted. From the multiple Olympic triumphs, through to her winning both the GM title and the Women’s World Championship, and her coaching journey in US universities, every chapter of this book is fascinating. Hopefully this review has whetted your appetite. A remarkable story, a remarkable family, a remarkable person! Susan Polgar is truly a Rebel Queen. Go out and buy it.