Book of the Month by Ben Graff

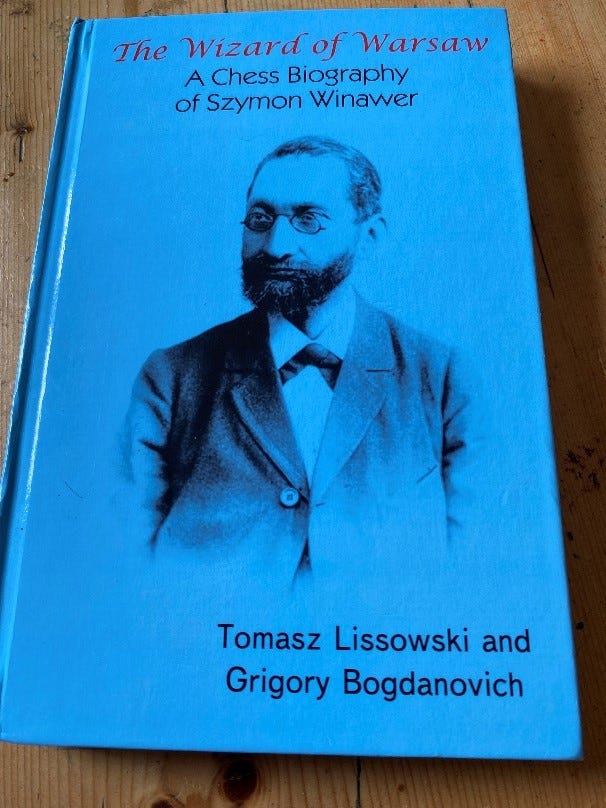

The Wizard of Warsaw – A Chess Biography of Szymon Winawer by Tomasz Lissowski and Grigory Bogdanovich (Elk and Ruby)

‘I can’t help but remember Winawer’s courteous, knightly art of building friendly bridges with his desperate opponents when he was on the verge of victory. He showed no hint of arrogance or disrespect towards his opponents, but always found some kind words to sweeten their defeat.’

Andreas Ascharin, Schach-Humoresken, Riga 1894

In the unlikely event that I were ever rich enough to own a string of racehorses, I would undoubtedly name them all after chess openings. Wouldn’t it be good to see Ruy Lopez winning the Grand National, or Benko Gambit triumph in the Derby? Perhaps Winawer Variation might do well too. Yet how much do we know about the people who gave their names to our favourite systems? I had certainly played 3… Bb4 on many occasions in the French defence, but knew very little of Szymon Winawer’s story. This timely and fascinating translation of a book, first published in Russian, taught me a lot.

The age we live in now is very different from that of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Back then, chess memoirs were a rarity, and we often have little to go on in terms of understanding our forebearers’ innermost thoughts and feelings. The fact that Winawer appears by most accounts to have been ‘quiet and unobtrusive,’ with one contemporary going so far as to remark that ‘Winawer is so stingy with words that he usually doesn’t even announce his checks,’ makes clear the challenge faced by his biographers. Yet by drawing on the historical records, press reports and other accounts, as well as many of Winawer’s games, the authors undoubtedly succeed in developing an interesting picture of Winawer’s life in chess.

Growing up in a house where the game was ‘strictly forbidden’, as his mother thought chess ‘stole time,’ Winawer did not start playing until he was twenty, and by the age of thirty still did not have a single published game. In his early years, Winawer worked as a merchant by day, while honing his skills in the Warsaw chess cafés by night. Yet he possessed the most important commodity of them all in spades - namely an abundance of natural talent.

Winawer’s international chess debut was one that most of us could only dream about. In 1867, unknown outside Poland, he signed up for the Champ De Mars tournament in Paris, where many of the world’s finest players, including Steinitz, Neumann and Kolisch, were competing. Having arrived early for the event, Winawer headed for the Café de la Régence, where the unsuspecting Rosenthal offered him knight odds and promptly lost to the new player on the block. Stories suggest that Winawer took on others in Parisian cafés, dispatching them easily, only to find to his amazement that, rather than being the patzers he assumed, they were famous players.

In the tournament itself Winawer ultimately came in second, ahead of Steinitz, but behind Kolisch. However, suspicion lingers that Winawer should have won the event outright, as his last-round defeat against Rousseau was the subject of (unproven) speculation that Rousseau may have been assisted in some way. Moreover, the lack of time Winawer spent on his moves does appear a little odd. We will never know for sure, but what was beyond doubt was that Winawer had announced himself as one of the strongest players of his era.

This was an event where draws were considered a defeat for both players, in an era where analysing adjourned games was frowned on, if not forbidden. In essence, chess was on the cusp of its transition from the coffee house to the tournament arena of the modern-day game, and Winawer was undoubtedly in the vanguard of players competing when this step change came about. Perhaps his smoking habits also helped him to some extent as it is noted that ‘He smokes as a rule a brand of cigars known in Germany by the name of “outpost cigars”, because the aroma is so offensive that they can only be smoked in the open air.’ Winawer once remarked that if he could get his hands on even fouler cigars he would most likely win even more!

From Vienna to Warsaw, to London, Hastings, Berlin and many other places, this book charts Winawer’s competitive journey and includes many fascinating games within the main body of the work. In Part II, more than a hundred further pages are dedicated to Winawer’s games, covering his style, positional, tactical, endgame and opening play, as well as his ‘glorious defeats’ and his last recorded effort.

Very often a chess player’s strengths and weaknesses are two sides of the same coin, and so it is with Winawer. In many ways the game came too easily to him. It appears that he did not study much, and his knowledge of opening theory, even within the context of his era, was limited and often cost him. A Warsaw newspaper noted that ‘Winawer is called a “natural” player; they say he still hasn’t learned all the rules and secret theories of the game.’ Isidor Gunsberg further observed of Winawer that ‘he does not possess great powers of concentration necessary for heavy match play. On the other hand, he possesses a ready wit in his play, sees every possible chance at the board (because he does not concentrate his mind too intensely on single points or lines of play), and displays great skill and ingenuity when he sees his opportunity to initiate a combination.’

When a challenger was needed for Steinitz’s 1888 title match, Winawer’s was one of the first names to ‘crop up,’ but he was considered not to be in good enough health and, as with all of us, time ultimately diminished Winawer’s returns at the board.

The Wizard of Warsaw – A Chess Biography of Szymon Winawer does a brilliant job of painting a picture of this quiet man, who apparently did not even keep a chess set in his house. He may not have been talkative, but he was not devoid of wit. Remarking, when giving the shortest of toasts at the London event in 1883, ‘Gentlemen, if I speak Polish, you won’t understand me, and if I speak English, you won’t understand me either. So, thank you.’ This was someone who was happy to play players of all levels, and to give generous odds in these games. A true chess player’s chess player, through and through.

If there is a challenge with this book, it is one that is not fair to level at the authors. Namely, Winawer the man inevitably remains something of an enigma. It is mentioned that he outlived his wife and three of his sons, but there is little on the effect that this must have had on him. Yet, as we have already noted, this was a different epoch, where such things were not talked about and reflected on as they would be today. It is his on the board life where The Wizard of Warsaw excels.

Winawer was both a man of his time and a chess player who joins the ranks of those who transcend time. He will always be remembered, and this biography is an excellent way to learn more. The next time you play 3…Bb4 in the French, think of Winawer and his cigars. A brilliant natural talent, who got close, without going all the way, and left a lasting legacy.