Gawain Jones (1987-)

Gawain Jones was born on 11th December 1987 in Keighley, West Yorkshire. He started to play chess at the age of four, and made early headlines when at the age of nine he beat IM Malcolm Pein in a rapidplay. Gawain’s FIDE rating started at 2300 in 2003, and quickly increased. He gained the grandmaster title in 2007 after several strong performances in the 2006/2007 period, broke the 2600 barrier in 2011, and reached his personal best rating of 2709 in 2019. Gawain has won the British Championship three times, in 2012, 2017 and most recently in 2024, while also taking the top spot at Hastings 2012/3.

He has also had many tournament successes abroad, winning the Commonwealth Championship in 2011 and finishing first at the strong Dubai Open in 2016 and 2017. Gawain has also played regularly for the England team in Olympiads and other events, perhaps his best result being a silver medal on board 4 at the 2019 World Team Championship in Astana.

Gawain spent some years in Australasia, and lived in Wellington, New Zealand for a time. In 2012 he married Sue Maroroa Jones, herself a strong player, and the couple eventually settled in Sheffield and started a family. I was captain of the men’s team at the Batumi Olympiad in 2018, where both Gawain and Sue were playing for England. It was a pleasure to be with them, and as a captain I couldn’t have wished for a more cooperative team member than Gawain. The tragic death of Sue in May 2023 shocked the whole chess world, and not surprisingly Gawain took some time away from chess. However, in 2024 he returned to active play in the 4NCL, and as mentioned above notched up a win in the British Championship.

Having looked at many of Gawain’s games, I am reminded of an incident from long ago. After I had won against Susan Polgar, she commented that, when preparing for the encounter, she played over many of my games and noticed one common feature.

‘What was that?’, I asked.

‘In most of them you were lost at some point’, replied Susan.

It was not quite so extreme with Gawain, but I was struck by how often he wriggled out of dubious positions by continually creating problems for his opponent until they eventually went wrong. Of course, it's also possible that being lost at some point is part and parcel of playing the King’s Indian!

In this series I have tried to choose games which best illuminate a player’s style, rather than those with typical ‘best game’ sacrificial attacks. I think the following is a good example of Gawain’s combative and gritty style.

Gawain Jones - Andrey Esipenko

French Team Championship (Top 16) 2022

Scotch Opening

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 The Scotch Opening is not often seen these days, but some GMs use it as an occasional surprise weapon.

3...exd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nxc6 The older Scotch Four Knights with 5.Nc3 was once the main line, but the exchange on c6 was popularised by Kasparov in the 1990s. Although he won several games against strong opponents, this was due more to his innate talent than any special merits of the opening. However, even openings which are not theoretically critical can be effective when they are unexpected.

5...bxc6 6.e5 Qe7 7.Qe2 Nd5 8.h4 Kasparov preferred 8.c4, but according to current theory the line 8...Ba6 9.b3 g6 offers White no chance of an advantage, so attention switched to the odd-looking h-pawn advance. While this gives White the option of Rh3, objectively speaking it’s no better than 8.c4.

8...f6 One of a wide range of satisfactory moves: 8...Qe6, 8...a5 and 8...g6 also lead to an equal position.

9.c4 Ba6 Black develops a piece and keeps his knight in an active central position.

10.Rh3

Otherwise playing h4 makes little sense.

10...Nb6 Safer than 10...fxe5 11.Bg5 Nf6 12.Re3 0-0-0 13.Ra3, which leads to a very double-edged position.

11.Nd2 This pawn sacrifice is sharper than 11.exf6 Qxe2+ 12.Bxe2 Bxc4 13.fxg7 Bxg7 14.Bh5+ Kd8 15.Nc3, which results in a roughly level ending. However, it is more double-edged, as there is no guarantee that White will regain the pawn.

11...fxe5 12.Re3 First driving the bishop back by 12.Ra3 Bb7 13.Re3 is tempting, but giving up the potential gain of tempo by Ra3 is a concession, and after 13...0-0-0 Black is at least equal.

12...d6 13.g3 Defending the h-pawn, and preparing either Bg2 to put pressure on c6 or Bh3 to prevent castling.

13...Qd7 13...0-0-0? is a serious mistake, since 14.Ra3! Bb7 15.Nb3 wins for White; if Black deals with the threat of Bg5 by 15...h6, then 16.Rxa7 Kb8 17.Rxb7+ Kxb7 18.Na5+ gives White a decisive attack. The move played still doesn’t threaten 14...0-0-0, as 15.Ra3 remains a dangerous reply; rather, the idea is ...Be7 followed by kingside castling.

14.Ra3 White must play vigorously to justify his pawn sacrifice. For the moment Black’s king is stuck in the centre, so White tries to open lines to give his pieces more attacking potential. The main difficulties are that White’s development is far from complete, and that if Black does solve the problem of his king position it may well be White’s king which is stuck in the centre. Objectively speaking, White has enough for the pawn but no more; however, in such a sharp position even a small inaccuracy can have serious consequences.

14...Bc8 Better than 14...Bb7 15.c5 Nd5 16.Nc4, which leaves the b7-bishop totally blocked in.

15.c5 Nd5 16.Ne4 Be7 Black continues with his preparations for kingside castling.

17.Qh5+ Forcing ...g6, providing a square on h6 for the c1-bishop, which otherwise doesn’t have a tempting developing move.

17...g6 18.Qd1 In a later game Acs-S. Sargsyan (Sharjah 2023) White tried 18.Qe2 a5 19.Bh6 Qg4 20.f3 Qe6, and now 21.Qd2 would have given White a definite advantage, since 22.Rxa5 and 22.Bc4 are both threatened. However, Black could have improved earlier, for example by 18...0-0 as in the current game.

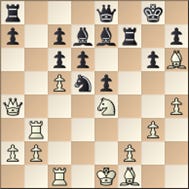

18...0-0 19.Bh6 Rf7 20.Qa4

It’s a tribute to the concrete nature of contemporary chess that both sides seem to be flouting basic principles taught to beginners, such as not moving the same pieces repeatedly, completing development, and castling quickly. The tendency to prefer the definite over the general was evident even before the advent of computers, but the extensive use of engines in pre-game preparation has greatly accelerated the trend: when the machine says ‘jump’, players generally jump.

20...Qe8 21.Rc1 A controversial decision as 21.0-0-0 looks more natural, and would have led to a balanced position. Leaving the king in the centre appears riskier, but at least White keeps open the option of Kf1-g1 to reach a safe position on the kingside.

21...Bd7 The greedy 21...dxc5 22.Bc4 Bf5 looks more to the point. Black’s pawn structure is a wreck, but he has two more than White.

22.Rb3 White hopes to play Rb7, but it all looks a bit slow. 22.Bc4 Be6 23.Kf1 seems better, when at least there’s an amusing symmetry in that earlier both sides appeared to be aiming for queenside castling, but both ended up shuffling their kings to the kingside.

22...Bf8 The ingenious machine suggestion 22...Nb6!? 23.Qa6 (23.cxb6 axb6 24.Qb4 d5 also slightly favours Black) 23...d5 24.cxb6 axb6 25.Qb7 dxe4 26.Bc4 Bd6 involves Black giving up the exchange to sideline the white queen and take over the initiative. This may indeed be Black’s best line, and is sufficient for an edge.

23.Bxf8 Qxf8 24.cxd6 cxd6 25.Qa3 At last White has a concrete threat. There’s no realistic way to defend the d6-pawn, since 25...c5 26.Bc4 Bc6 27.Rd3 wins material. If the d-pawn falls without compensation, White will have the advantage based on his well-placed knight and Black’s three isolated pawns.

25...Rd8 Up to here the game has been balanced, but now Black starts to lose his way. 25...Nb6! 26.Qxd6 Rxf2 27.Qxf8+ Rfxf8 was safest, when Black retains his extra pawn, and although White has enough positional compensation Black is not worse.

26.Rb7 26.Qxd6 Rxf2 is similar to the last note, but White need not take on d6 straight away. First he improves his rook position, and hopes to win the a7-pawn as well.

26...Rf3? Also not 26...Be6? 27.Rxf7 Bxf7 28.Rxc6, which is even worse for Black. The best line was 26...Ne7! 27.Nxd6 (27.Qxd6? loses to 27...Bc8) 27...Rxf2 28.Bc4+ Nd5 29.Qc5 Rh2 30.Bxd5+ cxd5 31.Qxd5+ Kg7 32.Qxe5+ Kh6, with a likely perpetual check.

27.Qxd6? Missing his chance. The surprising line 27.Qa5! (threatening 28.Bc4) 27...Ne7 28.Qxa7 Nc8 29.Qa5 would have been very strong, when White restores material equality while retaining strong pressure. Then it’s important that the natural 29...d5 fails to 30.Be2! dxe4 31.Bc4+ Kh8 32.Rd1 with a deadly attack, but this line is admittedly hard to see in advance.

27...Rxf2 28.Bc4 Qxd6 29.Nxd6 Rf6 29...Rf3 30.Rxa7 Be6 31.Nb7 Rb8 is also roughly equal.

30.Ne4 Rf7 31.Ng5 Re7 32.Rd1 Rf8? The long period of defence in a very complicated position finally takes its toll on Black, and he makes a serious mistake. He could still have saved the game by 32...Rde8! unpinning the d7-bishop. Then 33.Bxd5+ (33.Rxa7 Bf5 leads to a similar simplification; the two connected passed pawns are too far back to pose a real danger) 33...cxd5 34.Rxd5 Bc6 35.Rxe7 Rxe7 36.Rd6 Bd7 37.Ke2 Bf5 is safe for Black.

33.Rxa7 White regains the sacrificed pawn, while retaining strong pressure.

33...h6 34.Ne4 Kh8 35.Bxd5 cxd5 36.Rxd5 Rf1+ Black avoids losing further material, but it does not save the game.

37.Kd2 Rd1+ 38.Kxd1 Bg4+ 39.Kd2 Rxa7 40.a3 Now White is clearly winning.

40...Re7 41.b4 Kg7 42.a4 1-0